Voter Registration#

Every state has a unique approach to voter registration —- including some states with automatic voter registration —- but there are several commonalities shared by all of them. Voter registration systems provide voters with the opportunity to establish their eligibility and right to vote, and for states and local jurisdictions to maintain each voter’s record, often including assigning voters to the correct polling location. Voter registration systems support pollbooks—paper and electronic—as well as provide information back to the voter as they verify their registration and look up polling locations and sample ballots.

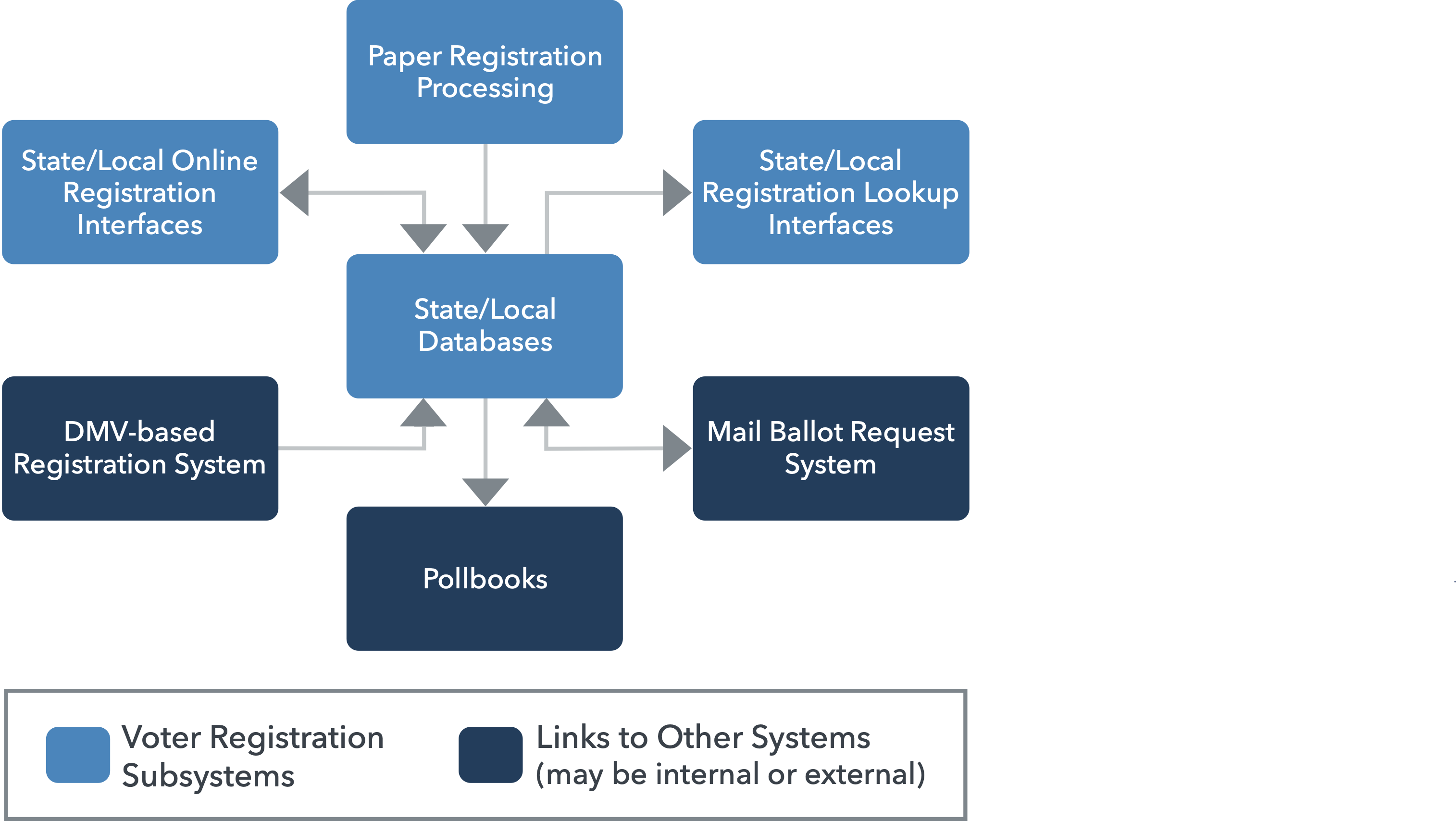

The inputs to voter registration systems are registrations, removals due to ineligibility (e.g., an individual moving out of state, death of an individual), and record updates, most often due to an individual moving within the state. The outputs include facilitating voter lookups—-such as a voter verifying they are registered, seeking a sample ballot, or finding their polling place—-and transfer of voter information to pollbooks. By their nature, that means voter registration systems are not only critical to election administration, but include personal information such as name, birth date, and postal address.

In each of these cases, there is a master voter database at the state level. This database is populated in one of three broad ways (lightly edited from the Election Assistance Commission’s 2014 Statutory Overview):

A top-down system in which the data are hosted on a single, central platform of hardware and maintained by the state with data and information supplied by local jurisdictions,

A bottom-up system in which the data are hosted on local jurisdictions’ hardware and periodically compiled to form a statewide voter registration list, or

A hybrid approach, which is a combination of a top-down and bottom-up system.

For all three cases, voter registration systems consist of one or more applications that leverage general-purpose computing systems built on commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) hardware, software, and cloud services. Because they use these common computing platforms, voter registration systems may be part of a shared computing system, though in many cases they are dedicated systems with dedicated software.

While jurisdictions vary in how they allow voters to apply or update their registration, in many states, the most common way voters access a registration system is through the state’s department of motor vehicles (DMV). Additionally, voters’ connection to the voter registration system may run through direct means such as a county or state registration portal, or through indirect means like mailing in a registration on paper. To address this risk, many voter registration systems with which the voter would interact are separated from the “official,” or production, voter registration system. Periodically, a report of changes is generated and undergoes a quality assurance review that must be certified before being entered into the production system. This can substantially reduce, for instance, an online portal as a vector of attack, though the production system may still be network connected in other ways.

In general, voter registration systems exhibit the risk characteristics of a general-purpose computing system and, more specifically, any network connected database application. To properly mitigate risks, each voter registration system within a state, and links to the voter registration system, needs a comprehensive assessment of its technical characteristics and the application of appropriate security controls.

Types of voter registration systems#

Voter registration generally occurs in one of two ways, each of which is recorded in a statewide registration system.

Online registration: a website or other web application allows prospective voters to register electronically and have election officials review their registration for validity, which, if valid, is entered into the voter registration database. Same-day registration, because of the need for live updating and cross checking, usually falls into this category.

Paper-based registration: prospective voters submit a paper voter registration form that is reviewed by election officials and, if valid, entered into the voter registration database.

The type of voter registration employed at DMVs will vary by state—and perhaps locality—but should typically be viewed as a form of online registration.

Risks and threats#

As noted in the previous section, the ability to access voter registration systems through the internet results in a significant increase in vulnerability and resulting risk. There are well known best practices to mitigate these risks (see many of the best practices in this Guide, especially here and here), but the ability to attack and manipulate voter registration systems by remote means makes them a priority for strengthening of the security resilience of these components.

While attacks on voter registration systems may have a specific purpose not found outside the elections domain, the vectors for those attacks, and thus the primary risks and threats associated with voter registration systems, are similar to those of other systems running on COTS IT hardware, software, or cloud systems, and include:

Risks associated with established (whether persistent or intermittent) internet connectivity;

Network connections with other internal systems, some of which may be owned or operated by other organizations or authorities;

Security weaknesses in the underlying COTS products, whether hardware, software or cloud systems;

Errors in properly managing authentication and access control for authorized users;

Difficulty associated with finding, and rolling back, improper changes found after the fact;

Infrastructure- and process-related issues associated with backup and auditing; and

Vulnerabilities resulting from misconfigurations.

These items must be managed to ensure proper management of voter registration systems. Because they are risks and threats shared among users of COTS products, there is a well-established set of controls to mitigate risk and thwart threats, as provided throughout this Guide and in related cyberscurity guidance such as the CIS Controls.

How these components connect#

Each type of voter registration, along with the master voter registration database, should have risks evaluated individually based on its type of connectivity and employ controls and best practices found throughout this Guide that correspond to the type of connectivity and are appropriate to address risks. That said, aspects of the voter registration systems, and the types that may be implemented, have general characteristics that can be classified by connectivity.

Connectedness |

System Type and Additional Information |

|---|---|

Network Connected |

Online Registration. In addition, the master registration database, system itself, and online voter lookups should be considered network connected. |

Indirectly Connected |

Not applicable in most voter registration implementations. |

Not Connected |

Paper-based registration. |

Additional Transmission-based Risks |

Transmission of a registration via email or fax leverages a digital component. |